Note: The content of this page is available with proper page margins and padding at http://personality-politics.org/russia for improved readability.

March 14, 2022 — USPP releases updated threat assessment

Scroll to the bottom of this page or the http://personality-politics.org/russia page for an updated threat assessment in the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

The Political Personality of Russian Federation President Vladimir Putin. Working paper, Unit for the Study of Personality in Politics, January 2017. Abstract and link for full-text (38 pages; PDF) download at Digital Commons: http://digitalcommons.csbsju.edu/psychology_pubs/104/

The Personality Profile of Russian President

Vladimir Vladimirovich Putin

(Влади́мир Влади́мирович Пу́тин)

Aubrey Immelman

Unit for the Study of Personality in Politics

March 2014

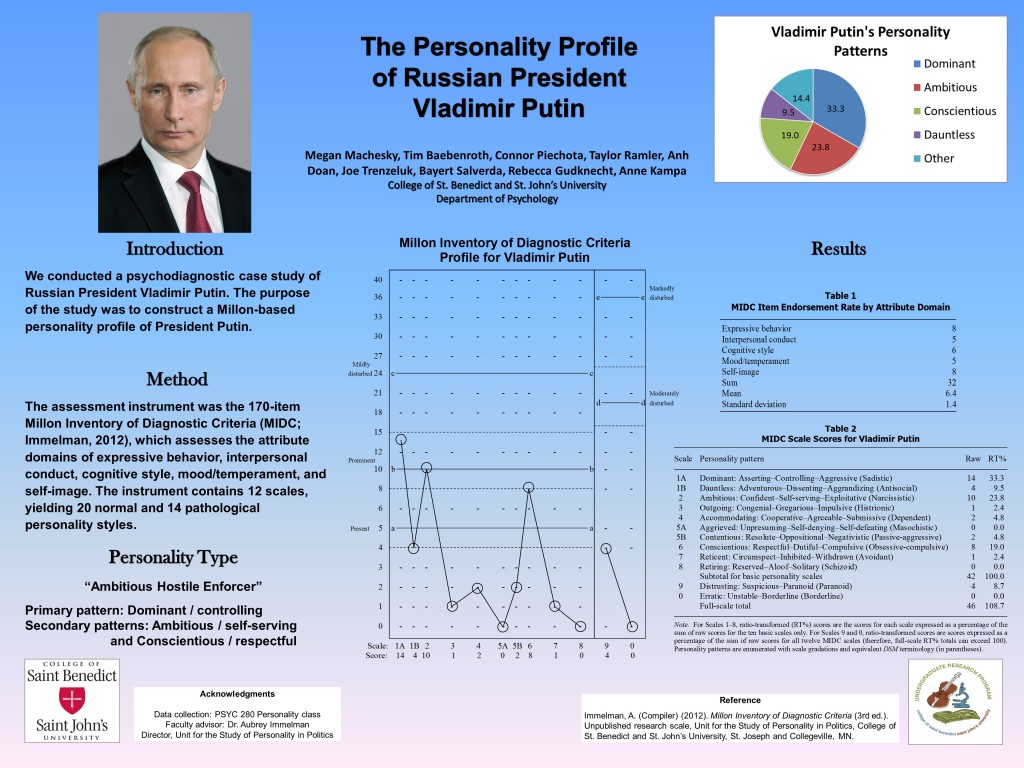

A remotely conducted empirical psychological assessment of Russian leader Vladimir Putin is currently in progress, using the third edition of the Millon Inventory of Diagnostic Criteria (MIDC), which yields 34 normal and maladaptive personality classifications congruent with DSM-IV.

Informal observation suggests that Putin is a highly dominant leader. However, more systematic observation is required to establish whether he is an introvert or an extravert.

If Putin is a dominant introvert, which appears to be the case [confirmed 7/30/2014], the following personality-based leadership profile would apply:

In terms of Lloyd Etheredge’s (1978) fourfold typology of personality-based foreign policy role orientations, which locates policymakers on the dimensions of dominance–submission and introversion–extraversion, high-dominance introverts (in American politics, presidents such as Woodrow Wilson and Herbert Hoover) are quite willing to use military force, tending

to divide the world, in their thought, between the moral values they think it ought to exhibit and the forces opposed to this vision. They tend to have a strong, almost Manichean, moral component to their views. They tend to be described as stubborn and tenacious. They seek to reshape the world in accordance with their personal vision, and their foreign policies are often characterized by the tenaciousness with which they advance one central idea. … [These leaders] seem relatively preoccupied with themes of exclusion, the establishment of institutions or principles to keep potentially disruptive forces in check. (p. 449; italics in original)

Etheredge’s high-dominance introvert is similar in character to Margaret Hermann’s (1987) expansionist orientation to foreign affairs. These leaders have a view of the world as being “divided into ‘us’ and ‘them,’” based on a belief system in which conflict is viewed as inherent in the international system. This world view prompts a personal political style characterized by a “wariness of others’ motives” and a directive, controlling interpersonal orientation, resulting in a foreign policy “focused on issues of security and status,” favoring “low-commitment actions” and espousing “short-term, immediate change in the international arena.” Expansionist leaders “are not averse to using the ‘enemy’ as a scapegoat” and their rhetoric often may be “hostile in tone” (pp. 168–169).

References

Etheredge, L. S. (1978). Personality effects on American foreign policy, 1898–1968: A test of interpersonal generalization theory. American Political Science Review, 72, 434–451.

Hermann, M. G. (1987). Assessing the foreign policy role orientations of sub-Saharan African leaders. In S. G. Walker (Ed.), Role theory and foreign policy analysis (pp. 161–198). Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Pilot Study — April 25, 2014

Click on image for larger view

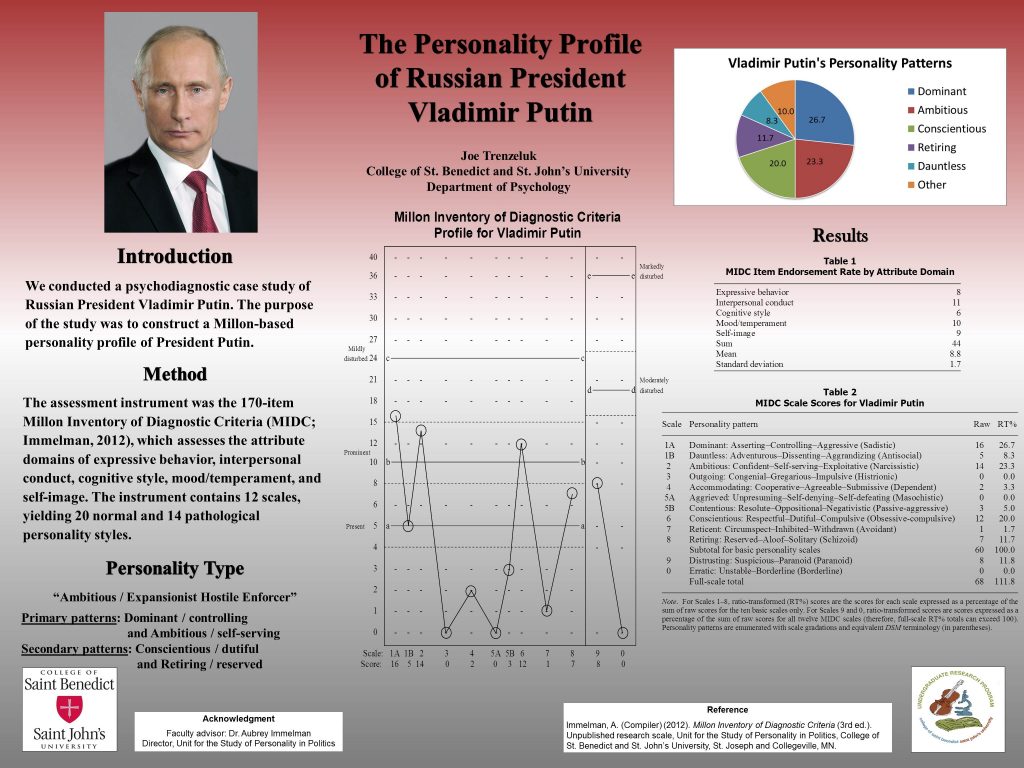

Full Study — July 30, 2014

Following additional data collection by summer research fellow Joe Trenzeluk during the months of June and July, the psychological assessment of Russian leader Vladimir Putin has been completed. The next phase of the study, to be conducted during the month of August, will be to elaborate on Putin’s leadership style, employing his personality profile as a temporally and cross-situationally stable framework for anticipating his future political behavior.

Click on image for larger view

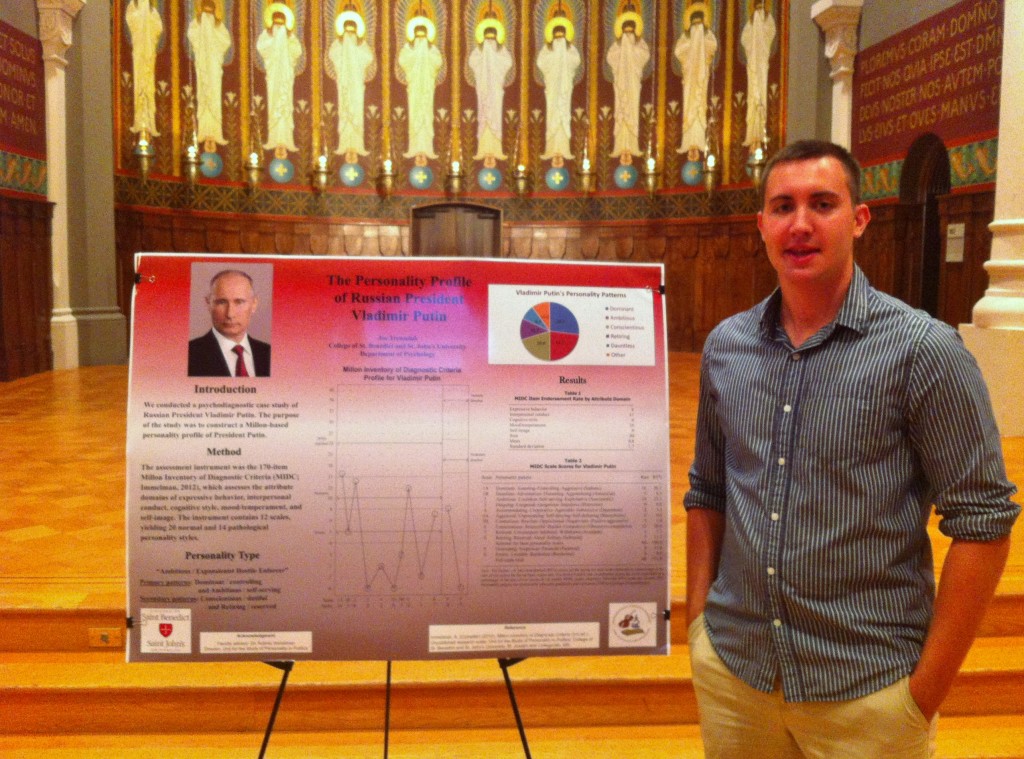

Joe Trenzeluk presents his research on “The personality profile of Russian president Vladimir Putin” at the Undergraduate Research Poster Session, Great Hall, St. John’s University, Collegeville, Minn., Aug. 6, 2014.

Research report — January 5, 2017

The Political Personality Personality of Russian Federation President

Vladimir Putin

(Владимир Путин)

Aubrey Immelman and Joseph V. Trenzeluk

Unit for the Study of Personality in Politics

January 2017

Abstract

This paper presents the results of an indirect assessment of the personality of Vladimir Putin, president of the Russian Federation, from the conceptual perspective of personologist Theodore Millon.

Psychodiagnostically relevant data regarding President Putin was extracted from open-source intelligence and synthesized into a personality profile using the Millon Inventory of Diagnostic Criteria (MIDC), which yields 34 normal and maladaptive personality classifications congruent with Axis II of DSM-IV.

The personality profile yielded by the MIDC was analyzed on the basis of interpretive guidelines provided in the MIDC and Millon Index of Personality Styles manuals. Putin’s primary personality patterns were found to be Dominant/controlling (a measure of aggression or hostility), Ambitious/self-serving (a measure of narcissism), and Conscientious/dutiful, with secondary Retiring/reserved (introverted) and Dauntless/adventurous (risk-taking) tendencies and lesser Distrusting/suspicious features. The blend of primary patterns in Putin’s profile constitutes a composite personality type aptly described as an expansionist hostile enforcer.

Dominant individuals enjoy the power to direct others and to evoke obedience and respect; they are tough and unsentimental and often make effective leaders. This personality pattern comprises the “hostile” component of Putin’s personality composite.

Ambitious individuals are bold, competitive, and self-assured; they easily assume leadership roles, expect others to recognize their special qualities, and often act as though entitled. This personality pattern delineates the “expansionist” component of Putin’s personality composite.

Conscientious individuals are dutiful and diligent, with a strong work ethic and careful attention to detail; they are adept at crafting public policy but often lack the retail political skills required to consummate their policy objectives and are more technocratic than visionary. This personality pattern fashions the “enforcer” component of Putin’s personality composite.

Retiring (introverted) individuals tend not to develop strong ties to others, are somewhat deficient in the ability to recognize the needs or feelings of others, and may lack spontaneity and interpersonal vitality.

Dauntless individuals are adventurous, individualistic, daring personalities resistant to deterrence and inclined to take calculated risks.

Putin’s major personality-based strengths in a political role are his commanding demeanor and confident assertiveness. His major personality-based shortcomings are his uncompromising intransigence, lack of empathy and congeniality, and cognitive inflexibility.

Full-text download » http://digitalcommons.csbsju.edu/psychology_pubs/104/

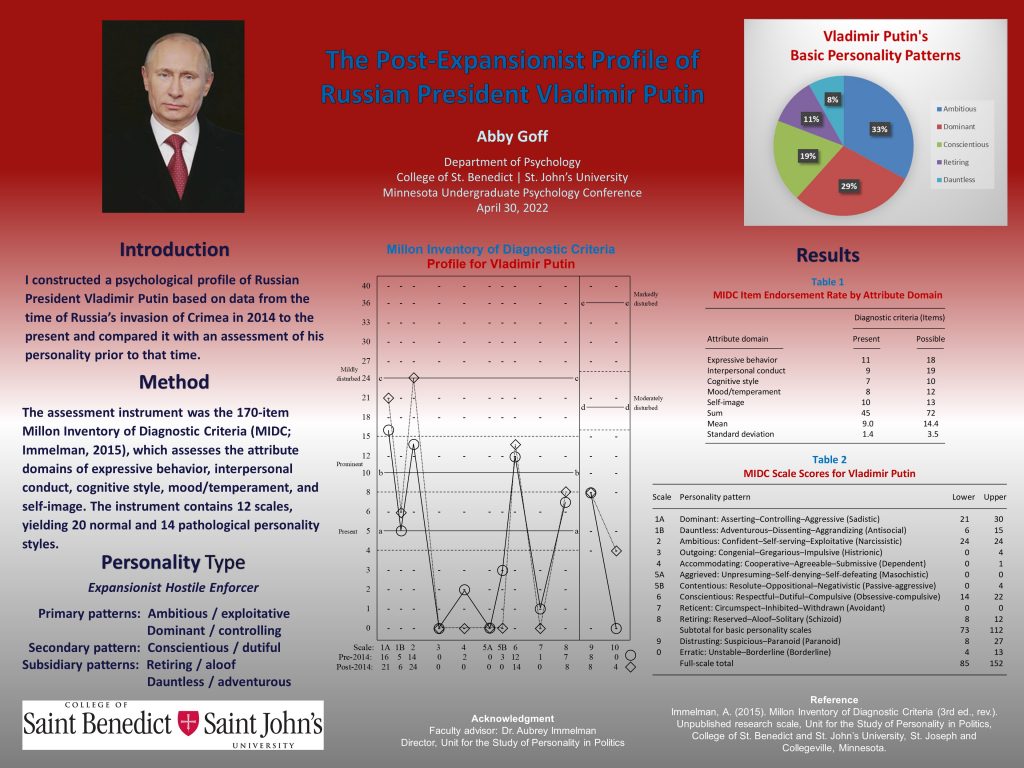

Research presentation — April 30, 2022

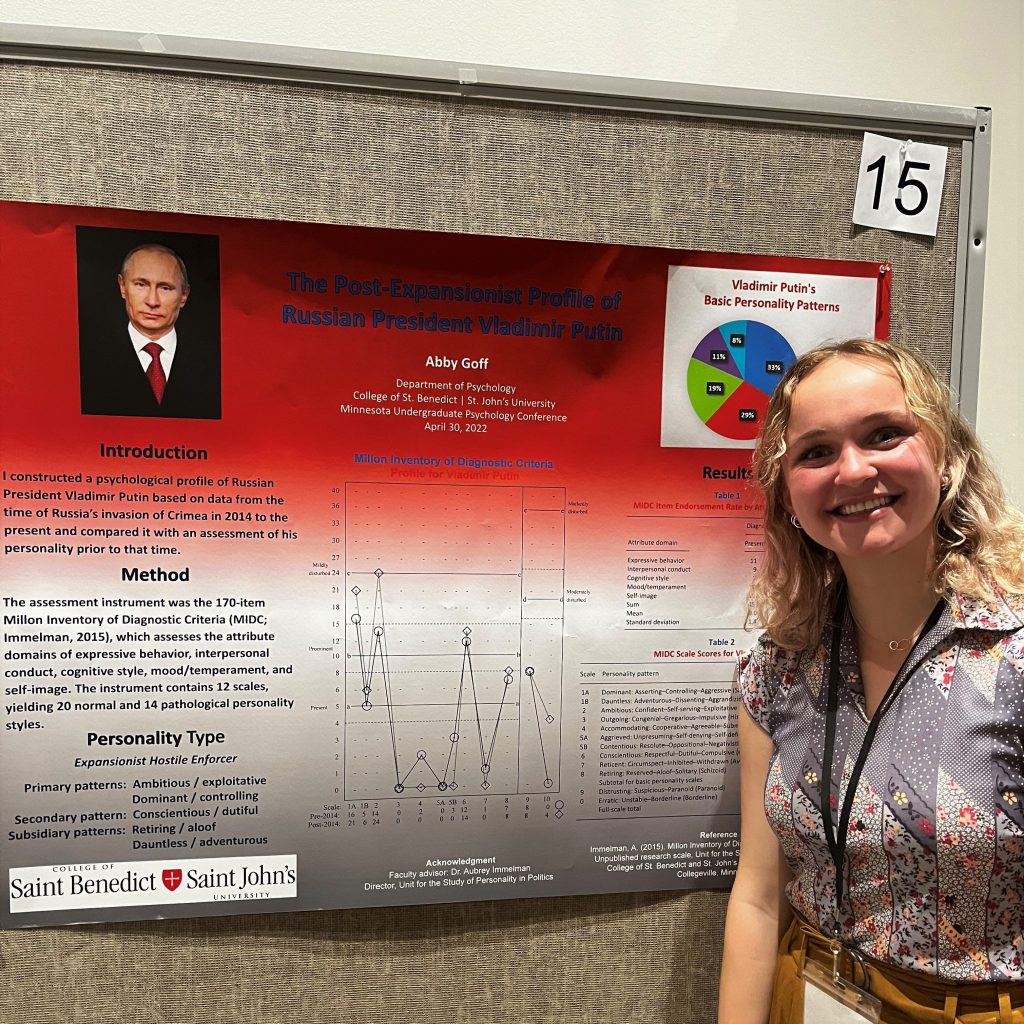

Abby Goff presents her research poster on “The Post-Expansionist Profile of Russian President Vladimir Putin” at the Minnesota Undergraduate Psychology Conference, Macalester College, St. Paul, Minnesota, April 30, 2022.

Click on image for larger view

Related reports

Putin Should Prepare Himself for Clinton (Joe Trenzeluk, St. Cloud Times, June 28, 2014) — The past few months have sparked heated debate regarding President Obama’s handling of foreign policy, specifically the crisis in Ukraine and his negotiations, or lack thereof, with Vladimir Putin. … Political-psychological studies suggest that putative 2016 presidential candidate Hillary Rodham Clinton may be better suited than Obama to deal with Putin. … Full report

Profile Hints at Putin Mindset (Joe Trenzeluk, St. Cloud Times, August 3, 2014) — On July 17, 298 innocent victims were killed when Malaysia Airlines Flight MH17 was shot down over Ukraine. As attempts to investigate the incident continue, international pressure has been placed on Russian President Vladimir Putin because it is believed the Russian military supplied Ukrainian pro-Russia separatists with the Buk surface-to-air missiles that downed the airliner. … Full report

The Many Faces of Vladimir Putin: A Political Psychology Profile (Kenneth Dekleva, The Cipher, January 22, 2017) — Many profiles of Putin have missed the mark, labeling him as a “thug” or seeing him as a mere tool of larger, more intricate power structures or groupings, such as the siloviki, Russia’s military, law-enforcement, and intelligence communities. Such analyses of Putin’s political behavior have at times led to a lack of predictive power regarding Russia’s actions or to heightened emotional predictions of a new Cold War or military conflict between Russia and the West. … Full report

SIDEBAR

The CIA’s secret psychological profiles of dictators and world leaders are amazing: Psychoanalyzing strongmen, from Castro to Saddam (Dave Gilson, Mother Jones, Feb. 11, 2015) — Last week, Politico and USA Today reported about a secret 2008 Pentagon study which concluded that Russian President Vladimir Putin’s defining characteristic is … autism. The Office of Net Assessment’s Body Leads project asserted that scrutinizing hours of Putin footage revealed “that the Russian President carries a neurological abnormality … identified by leading neuroscientists as Asperger’s Syndrome, an autistic disorder which affects all of his decisions.” Putin’s spokesman dismissed the claim as “stupidity not worthy of comment.” But it was far from the first time the intelligence community has tried to diagnose foreign leaders from afar on behalf of American politicians and diplomats. The CIA has a long history of crafting psychological and political profiles of international figures, with varying degrees of depth and accuracy. … Full story

Updated Threat Assessment

March 20, 2022

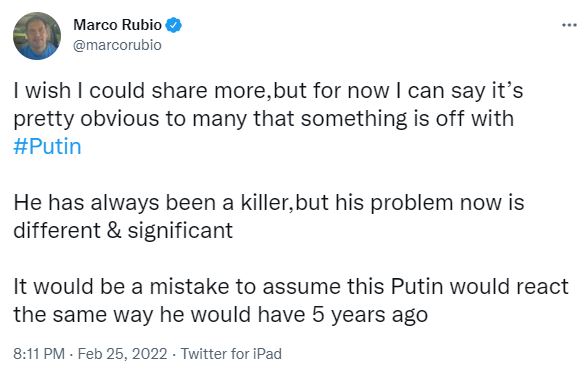

On February 25, 2022 – the day after Russia invaded Ukraine – U.S. Sen. Marco Rubio, a member of the “Gang of Eight” in Congress with access to the most sensitive classified intelligence information, tweeted, “I wish I could share more, but for now I can say it’s pretty obvious to many that something is off with #Putin. … It would be a mistake to assume this Putin would react the same way he would have 5 years ago.”

Rubio denied that his tweet referenced classified assessments of Vladimir Putin’s mental state by U.S. intelligence agencies; however, questions regarding Putin’s mental stability were reinforced by contemporaneous statements made by other public figures with past connections to the intelligence community.

For example, on February 27, Condoleezza Rice, former U.S. secretary of state in the George W. Bush administration, said on Fox News Sunday that Putin “seems erratic,” with “an ever deepening, delusional rendering of history.”

Concurrently, Fox News reported that James Clapper, former national intelligence director in the Obama administration, “echoed Rice’s assessment,” telling CNN Putin was “unhinged” and that he was worried about Putin’s “acuity and balance,” given that he has his finger on the nuclear trigger.

Furthermore, an unnamed “senior national security official” under former U.S. president Donald Trump told Fox News that when Putin met with French president Emmanuel Macron in February, “he seemed ‘paranoid.’ ”

Finally, for a contrary point of view, Fox News quoted former Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA) analyst Rebekah Koffler, author of Putin’s Playbook: Russia’s Secret Plan to Defeat America, as saying: “Putin is absolutely not crazy. … He’s not delusional, there are no mental anomalies. … Putin is a cold-blooded, typical Russian autocratic leader and a very calculated risk-taker. He’s simply executing a plan that he has been hatching for 20 years.”

Koffler’s analysis is congruent with the Unit for the Study of Personality in Politics’s (USPP) psychological profile of Putin. Moreover, her analysis aligns with Virginia Commonwealth University’s Wilder School of Government & Public Affairs assistant professor Benjamin R. Young’s exposition of Putin’s “Russkiy Mir” worldview, published in Foreign Policy on (March 6, 2022). Following is a summary of these two perspectives.

What is Putin’s personality profile and has it changed in the recent past?

A study conducted at the Unit for the Study of Personality in Politics in 2014 may be summarized as follows:

Putin’s primary personality patterns were found to be Dominant/controlling (a measure of aggression or hostility), Ambitious/self-serving (a measure of narcissism), and Conscientious/dutiful, with secondary Retiring/reserved (introverted) and Dauntless/adventurous (risk-taking) tendencies and lesser Distrusting/suspicious features. The blend of primary patterns in Putin’s profile constitutes a composite personality type aptly described as an expansionist hostile enforcer.

Dominant individuals enjoy the power to direct others and to evoke obedience and respect; they are tough and unsentimental and often make effective leaders. This personality pattern encapsulates the “hostile” component of Putin’s personality composite.

Ambitious individuals are bold, competitive, and self-assured; they easily assume leadership roles, expect others to recognize their special qualities, and often act as though entitled. This personality pattern reveals the “expansionist” component of Putin’s personality composite.

Conscientious individuals are dutiful and diligent, with a strong work ethic and careful attention to detail; they are adept at crafting public policy but often lack the retail political skills required to consummate their policy objectives and are more technocratic than visionary. This personality pattern fashions the “enforcer” component of Putin’s personality composite.

Retiring (introverted) individuals tend not to develop strong ties to others, are somewhat deficient in the ability to recognize the needs or feelings of others, and may lack spontaneity and interpersonal vitality.

Dauntless individuals are adventurous, individualistic, daring personalities resistant to deterrence and inclined to take calculated risks.

In theory, one would not expect any significant changes to Putin’s personality profile as assessed in 2014 because personality, by definition, refers to the ways a person’s thoughts (cognitions), emotions/feelings (affects), behaviors (actions), and mode of relating to others are stable over time and consistent over situations (i.e., temporal stability and cross-situational consistency).

However, it is possible for personality functioning – perhaps due to prolonged social isolation or chronic psychological stressors – to become compromised (decompensated) over time, shading into the sphere of mental illness.

For the purpose of risk assessment, plausible (though hypothetical) comorbidities of Putin’s primary personality patterns are outlined below:

MIDC Scale 1A: The Dominant Pattern

According to Theodore Millon (2011), Dominant (Assertive–Denigrating–Sadistic spectrum) personality types are notably predisposed to syndromes of a paranoidlike character: “Delusional disorders may occur owing to life’s circumstances that force the sadist into patterns of social withdrawal, and these may lead, in turn, to fixed ideas of a delusional nature.” (p. 646)

MIDC Scale 2: The Ambitious Pattern

According to Millon (2011), Ambitious (Confident–Egotistic–Narcissistic spectrum) personality types “may decompensate into paranoid disorders. Owing to their excessive use of fantasy mechanisms, they are disposed to misinterpret events and to construct delusional beliefs. Unwilling to accept constraints on their independence and unable to accept the viewpoints of others, narcissists may isolate themselves from the corrective effects of shared thinking. Alone, they may ruminate and weave their beliefs into a network of fanciful and totally invalid suspicions.” (pp. 407–408)

MIDC Scale 6: The Conscientious Pattern

According to Millon (2011), “the frequency of co-morbidity is perhaps the lowest” among Conscientious (Reliable–Constricted–Compulsive spectrum) personality types and “tends to be fairly circumscribed when compared with other personality disorders.” (p. 508)

Formulation

Two of Putin’s primary personality patterns delusional syndromes as potential comorbidities. A delusion may be defined as a false belief that is impervious to reason. In the context of political leadership, it may be instructive to examine potential delusional thinking on the part of Putin’s as a preexisting vulnerability rooted in his political ideology or, more specifically his worldview. In that regard, Young’s description of Putin’s view of the world is enlightening.

Putin’s Russkiy Mir worldview

According to Benjamin Young (2022),

Putin believes an invasion of Ukraine is a righteous cause and necessary for the dignity of the Russian civilization, which he sees as being genetically and historically superior to other Eastern European identities. The idea of protecting Russian-speakers in Eurasia has been a key part of Putin’s “Russkiy Mir” worldview and 21st-century Russian identity. Under the rubric of Russkiy Mir (Russian World), Putin’s government promotes the idea that Russia is not a mere nation-state but a civilization-state that has an important role to play in world history.

In 1997, Russian post-liberal, neo-fascist philosopher Alexander Dugin, later an advisor to Putin, published his foundational book, Foundations of Geopolitics. Referred to as Putin’s Rasputin, Dugin argues that the world order is shaped by competition between Sea Powers (Atlanticists), such as the United States, the United Kingdom, and the EU countries, and Land Powers (Eurasianists), such as Russia.

Dugin argues that Russia’s geopolitical position weakened after the collapse of the Soviet Union and that invasions of Georgia and Ukraine were necessary for tilting the world system back in Moscow’s favor. For Dugin, an invasion of Ukraine was the most important part of this civilizational battle between the sea-faring Atlanticists and the land power Eurasianists. “Ukraine, as an independent state with some territorial ambitions, poses a huge danger to the whole of Eurasia, and without solving the Ukrainian problem, it makes no sense to talk about continental geopolitics,” Dugin explained in his 1997 book. While Dugin’s closeness to Putin’s inner circle has varied throughout time, his ideas have permeated within elite Russian political and military circles. The recent invasion of Ukraine is a continuation of a Dugin-promoted strategy for weakening the international liberal order.

Along with Duginism, the Kremlin has circulated the ideas of Russkiy Mir within Russian media and civic society. Putin first publicly mentioned the term Russkiy Mir in 2001 at the first World Congress of Russian Compatriots Living Abroad. He said, “The notion of the Russian World extends far from Russia’s geographical borders and even far from the borders of the Russian ethnicity.” Revanchism and a belief in the sacred role of the Russian civilization in world history have become the defining element of 21st-century Russian identity. …

For Putin, the collapse of the Soviet Union was an ideological calamity not because he holds any torch for communism itself but because it spiritually distanced Russian-speakers from their motherland. … For a patriotic ideologue such as Putin, this separation of Russophones from their motherland was an existential threat to the survival of the great Russian civilization.

For the last 20 years, Putin has sought closer ties with Russophone “compatriots” in former Soviet republics and has occasionally used the concept of Russkiy Mir to justify the 2008 invasion of Georgia and the 2014 annexation of Crimea. In the Russkiy Mir worldview, Ukraine plays a special role. It is the cornerstone of Russian civilization and culture. … For the Kremlin, without a Russophone Ukraine, there is no Russian World.

Formulation

Considering that Putin has subscribed to the “Russkiy Mir” worldview for at least two decades, his political cognition appears to be more an obsession embedded in his Conscientious personality pattern than a delusion comorbid with his Dominant and Ambitious personality patterns. Stated differently, Putin’s invasion of Ukraine may be viewed more as compulsion driven than delusional or “paranoidal.”

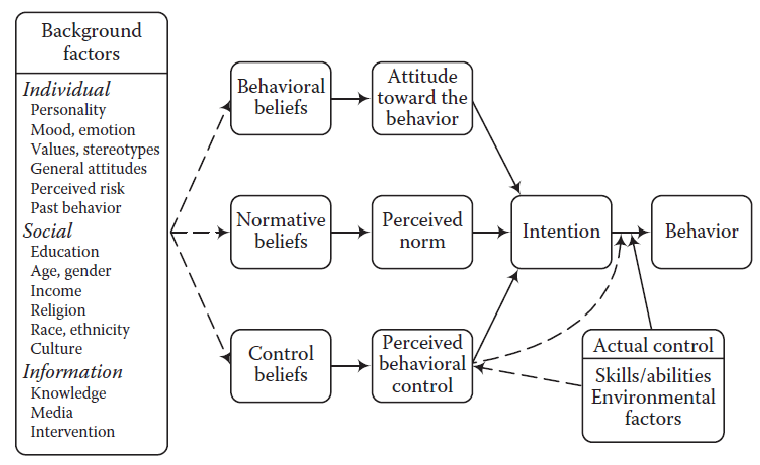

Person–Situation Interaction

There is no direct cause–effect relationship between personality and political behavior; behavior is a function of the internal dispositions of the person (including their ideological predispositions, worldview, personality traits, attitudes, and values) interacting with the external environment, or situation, which – following field theorist Kurt Lewin – may be summarized with the notation B = f(P × S).

Thus, it would be a mistake to attribute Putin’s actions exclusively to personological determinants (P) of political behavior (B). Based in research conducted at the USPP, it is plausible that a significant situational determinant (S) – effectively, a precipitating variable – of Putin’s decision to invade Ukraine is the transition from the administration of Donald Trump (the most aggressive and least accommodating U.S. president studied under the auspices of the USPP in the past three decades) to that of Joe Biden (the least aggressive, most accommodating/conciliatory president). If, indeed, Putin’s political calculus was informed by his perception of the current occupant of the White House as a risk-averse, conciliatory, nonconfrontational commander-in-chief, that perception could have been reinforced by the fiasco of the U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan in August 2021.

Empirical findings

According to Griebie and Immelman (2021), Joe Biden’s score of 3 on Scale 1A (Dominant) — a measure of aggressiveness — is the lowest score obtained by any major-party presidential candidate in the seven election cycles since 1996. In descending order of magnitude, the Scale 1A elevations of major-party presidential nominees studied at the Unit for the Study of Personality in Politics are: Donald Trump, 22 (2016, 2020; Immelman, 2016b); Hillary Clinton, 21 (2016; Immelman, 2016a); Bob Dole, 21 (1996; Immelman, 1998a); George W. Bush, 11 (2000; Immelman, 2002); John McCain, 10 (2008; Immelman, 2007); Al Gore, 8 (2000; Immelman, 1998b); Mitt Romney, 8 (2012; Immelman, 2012); Bill Clinton, 7 (1996; Immelman, 1998a); Barack Obama, 7 (2008, 2012; Immelman, 2010); John Kerry, 6 (2004; Immelman & Beatty, 2005); Joe Biden, 3 (2020; Griebie & Immelman, 2020).

Moreover, Griebie and Immelman (2021) note that Joe Biden’s score of 9 on MIDC scale 4 (Accommodating) — a measure of agreeableness — compares as follows with recent U.S. presidents: Barack Obama, 5 (Immelman, 2010); Bill Clinton, 5 (Immelman, 1998a); George W. Bush, 4 (Immelman, 2002); Donald Trump, 0 (Immelman, 2016b; Immelman & Griebie, 2020).

What if … Rubio and others are correct that Putin is “off,” “paranoid,” or “unhinged”?

Christopher S. Chivvis, a former U.S. intelligence official for Europe, recently wrote that “scores of war games carried out by the United States and its allies” all projected that Mr. Putin would launch a single nuclear strike if he faced limited fighting with NATO or major setbacks in Ukraine that he blamed on the West. (Max Fisher, “As Russia digs in, what’s the risk of nuclear War? The New York Times, March 16, 2022)

As political scientist Betty Glad wrote in a 2002 Political Psychology article titled “Why tyrants go too far: Malignant narcissism and absolute power”:

[A]bsolute power, paradoxically, is apt to result in even more extreme behavior. Even a malignant narcissist, in the climb to power, operates within certain external political constraints. But once he has attained absolute power, he can act out the grandiose fantasies that he had hitherto kept in some check. Fantasies, however, are not good guides to action. The individual under their pull is apt to overestimate his capabilities, fail to appreciate realistic obstacles in the external environment, and act in increasingly chaotic ways. As his cruelties and apparent erratic behaviors expand, he creates new enemies. Eventually, as he engages in ever more extreme behavior, his major psychological defense – paranoia – breaks down.

The particular finale to the tyrant’s story, however, will depend on the political structure in which he operates and the vicissitudes of fortune. If his extreme behavior leads to the creation of opposing alliances, new boundaries may keep his potential for fragmentation in check. But if he has undertaken a path that permits no face-saving exit, he may take a route that risks the structures he has built. Caught in a maelstrom of conflicting wishes and emotions and undertaking adventures for which there is no realistic productive end, the individual in such circumstances may seek some sort of way out. For those confronting such a leader, efforts should be made to maintain clear, firm, but non-provocative boundaries. Compromise with him is likely only to whet the appetite. But confrontations that humiliate him could lead to behavior that is destructive both to him and those threatening him. Short of keeping such a person from ever coming to power, the creation of countervailing constraints that are both clear and impersonally used may be the best alternative available. (pp. 33–34)

At what point do leaders reveal that they may not be of sound mind? To paraphrase Glad (2002), when the leader under the spell of narcissistic dreams of glory begins “to overestimate his capabilities, fail to appreciate realistic obstacles in the external environment, and act in increasingly chaotic ways” (p. 33) – to which one might add, when he fails to heed the counsel of his closest and most trusted advisers.

Within the parameters of the theoretical framework employed by Glad (2002) in her analysis of “why tyrants go too far,” the malignant narcissist’s

antisocial behavior is manifest in aggression or sadism directed against others or against himself through suicidal and self-destructive behavior. He also has strong tendencies toward paranoia (Kernberg, 1992, p. 81; Post, 1993, pp. 102–104), that is, “delusions of conspiracy and victimization” that are apt to be well concealed from those around him (Robins & Post, 1997, p. 4). The central defense of such a person, Volkan (1988, pp. 99–100, 201) argued, is splitting. Such a person maintains some sort of stability via a paranoid defense. He dichotomizes the world into good and evil elements, projecting his own dark side and vulnerabilities onto an external source, transforming an internal conflict into an external one. Thus, he is able to distance himself from an internal conflict by transforming that conflict into an external battle between himself as the representative of good and the scapegoat as the representative of evil. (p. 22)

Do attitudes predict behavior?

References

Fisher, M. (2022, March 16). As Russia digs in, what’s the risk of nuclear War? ‘It’s not zero.’ The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/03/16/world/europe/ukraine-russia-nuclear-war.html

Glad, B. (2002). Why tyrants go too far: Malignant narcissism and absolute power. Political Psychology, 23(1), 1–37.

Griebie, A., & Immelman, A. (2021, July). The personality profile and leadership style of U.S. president Joe Biden. Paper presented at the 44th Annual Scientific Meeting of the International Society of Political Psychology, July 11–13, 2021 (virtual conference). https://digitalcommons.csbsju.edu/psychology_pubs/132

Immelman, A. (1998a). The political personalities of 1996 U.S. presidential candidates Bill Clinton and Bob Dole. The Leadership Quarterly, 9(3), 335–366. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1048-9843(98)90035-2

Immelman, A. (1998b, July). The political personality of U.S. vice president Al Gore. Paper presented at the 21st Annual Scientific Meeting of the International Society of Political Psychology, Montréal, PQ, Canada, July 12–15, 1998. http://digitalcommons.csbsju.edu/psychology_pubs/37/

Immelman, A. (2002). The political personality of U.S. president George W. Bush. In L. O. Valenty & O. Feldman (Eds.), Political leadership for the new century: Personality and behavior among American leaders (pp. 81–103). Praeger.

Immelman, A. (2007, July). The political personalities of 2008 Republican presidential contenders John McCain and Rudy Giuliani. Paper presented at the 30th Annual Scientific Meeting of the International Society of Political Psychology, Portland, OR, July 4–7, 2007. http://digitalcommons.csbsju.edu/psychology_pubs/28/

Immelman, A. (2010, July). The political personality of U.S. president Barack Obama. Paper presented at the 33rd Annual Scientific Meeting of the International Society of Political Psychology, San Francisco, CA, July 7–10, 2010. http://digitalcommons.csbsju.edu/psychology_pubs/25/

Immelman, A. (2012, July). The political personality of 2012 Republican presidential candidate Mitt Romney. Paper presented at the 35th Annual Scientific Meeting of the International Society of Political Psychology, Chicago, IL, July 6–9, 2012. http://digitalcommons.csbsju.edu/psychology_pubs/98/

Immelman, A. (2016a, October). The political personality of 2016 Democratic presidential nominee Hillary Clinton. Collegeville and St. Joseph, MN: St. John’s University and the College of St. Benedict, Unit for the Study of Personality in Politics. http://digitalcommons.csbsju.edu/psychology_pubs/102/

Immelman, A. (2016b, October). The political personality of 2016 Republican presidential nominee Donald J. Trump. Paper presented at the 41st Annual Scientific Meeting of the International Society of Political Psychology, San Antonio, TX, July 4–7, 2018. http://digitalcommons.csbsju.edu/psychology_pubs/103/

Immelman, A., & Beatty, A. (2005, July). The political personality of 2004 Democratic presidential candidate John Kerry. Paper presented at the 28th Annual Scientific Meeting of the International Society of Political Psychology, Toronto, ON, July 3–6, 2005. http://digitalcommons.csbsju.edu/psychology_pubs/29/

Immelman, A., & Griebie, A. (2020, July). The personality profile and leadership style of U.S. president Donald J. Trump in office. Paper presented at the 43rd Annual Scientific Meeting of the International Society of Political Psychology, Berlin, Germany, July 14–16, 2020 (virtual conference). http://digitalcommons.csbsju.edu/psychology_pubs/129/

Millon, T. (2011). Disorders of personality: Introducing a DSM/ICD spectrum from normal to abnormal (3rd ed.). Wiley.

Young, B. R. (2022, March 6). Putin has a grimly absolute vision of the ‘Russian World.’ Foreign Policy. https://foreignpolicy.com/2022/03/06/russia-putin-civilization/