When Wilhelm Reich, the most brilliant of the second generation of psychoanalysts who had been Freud’s pupils, arrived in New York in August 1939, only a few days before the outbreak of war, he was optimistic that his ideas fusing sex and politics would be better received there than they had been in fascist Europe. Despite its veneer of puritanism, America was a country already much preoccupied with sex – as Alfred Kinsey’s renowned investigations, which he had begun the year before, were to show. However, it was only after the second world war that the idea of sexual liberation would permeate the culture at large. Reich could be said to have invented this “sexual revolution”; a Marxist analyst, he coined the phrase in the 1930s in order to illustrate his belief that a true political revolution would be possible only once sexual repression was overthrown. That was the one obstacle Reich felt had scuppered the efforts of the Bolsheviks. “A sexual revolution is in progress,” he declared, “and no power on earth will stop it.”

Reich was a sexual evangelist who held that satisfactory orgasm made the difference between sickness and health. It was the panacea for all ills, he thought, including the fascism that forced him from Europe. In his 1927 study The Function of the Orgasm, he concluded that “there is only one thing wrong with neurotic patients: the lack of full and repeated sexual satisfaction” (the italics are his). Seeking to reconcile psychoanalysis and Marxism, he argued that repression – which Freud came to believe was an inherent part of the human condition – could be shed, leading to what his critics dismissed as a “genital utopia” (they mocked him as “the prophet of bigger and better orgasms”). His sexual dogmatism got him kicked out of both the psychoanalytic movement and the Communist party. Nevertheless, Reich was a figurehead of the sex-reform movement in Vienna and Berlin – before the Nazis, who deemed it part of a Jewish conspiracy to undermine European society, crushed it. His books were burned in Germany along with those of Magnus Hirschfeld and Freud. Reich fled to Denmark, Sweden and then Norway, as fascism pursued him across the continent.

Soon after he arrived in the United States – by which time his former psychoanalytic colleagues were questioning his sanity – Reich invented the Orgone Energy Accumulator, a wooden cupboard about the size of a telephone booth, lined with metal and insulated with steel wool. It was a box in which, it might be said, his ideas about sex came almost prepackaged. Reich considered his orgone accumulator an almost magical device that could improve its users’ “orgastic potency” and, by extension, their general, and above all mental, health. He claimed that it could charge up the body with the life force that circulated in the atmosphere and which he christened “orgone energy”; in concentrated form, these mysterious currents could not only help dissolve repressions but treat cancer, radiation sickness and a host of minor ailments. As he saw it, the box’s organic material absorbed orgone energy, and the metal lining stopped it from escaping, acting as a “greenhouse” and, supposedly, causing a noticeable rise in temperature in the box.

The charismatic Reich persuaded Albert Einstein to investigate the machine, whose workings seemed to contradict all known principles of physics. After two weeks of tests Einstein refuted Reich’s claims. However, the orgone box became fashionable in America in the 1940s and 50s, and Reich grew increasingly notorious as the leader of the new sexual movement that seemed to be sweeping the country. The accumulator was used by such countercultural figureheads as Norman Mailer, JD Salinger, Saul Bellow, Paul Goodman, Allen Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac, Dwight Macdonald and William S Burroughs. In the 1970s Burroughs wrote an article for Oui magazine entitled “All the Accumulators I Have Owned”. In it, he boasted: “Your intrepid reporter, at age 37, achieved spontaneous orgasm, no hands, in an orgone accumulator built in an orange grove in Pharr, Texas.” At the height of his James Bond fame, Sean Connery swore by the device, and Woody Allen parodied it in Sleeper (1973), giving it the immortal nickname the “Orgasmatron”.

To bohemians, the orgone box was celebrated as a liberation machine, the wardrobe that would lead to utopia, while to conservatives it was Pandora’s box, out of which escaped the Freudian plague – the corrupting influence of anarchism and promiscuous sex. Reich’s eccentric device can be seen as a prism through which to look at the conflicts and controversies of his era, which witnessed an unprecedented politicisation of sex. When I first came across a reference to the accumulator, I was puzzled and fascinated: why on earth would a generation seek to shed its sexual repressions by climbing into a closet? And why were others so threatened by it? What does it tell us about the ironies of the sexual revolution that its symbol of liberation was a claustrophobic metal-lined box?

Because of his radical past, Reich was placed under surveillance almost as soon as he arrived in America and he was interned at the outbreak of war under suspicion of being a communist (his FBI file is 789 pages long). After the Soviet invasion of Finland, however, he became a committed anti-Stalinist. He rejected politics and now referred to the “self-regulating” sexual utopia of his imagination as “work-democracy”, which many of his fans among America’s avant-garde identified with eroticised anarchy.

In the ideological confusion of the postwar period, when the world was trying to understand the Holocaust, and intellectuals disillusioned with communism fled the security of their earlier political positions, Reich’s ideas landed on fertile ground. After the Hitler-Stalin pact and the Moscow trials, Reich’s theory of sexual repression seemed to offer the disenchanted left a convincing explanation both for large numbers of people having submitted to fascism and for communism’s failure to be a viable alternative to it. Reich, capturing the mood of this convulsive moment, presented guilty ex-Stalinists and former Trotskyites with an alternative programme of sexual freedom with which to combat those totalitarian threats. In his biography of Saul Bellow, who bought an orgone box in the early 50s and sat in it for daily irradiations, James Atlas wrote that “Reich’s Function of the Orgasm was as widely read in progressive circles as Trotsky’s Art and Revolution had been a decade before.”

In creating a morality out of pleasure, Reich allowed postwar radicals to view their promiscuity as political activism and justify their retreat from traditional politics. Reich made them feel part of the sexual elite, superior to the “frozen”, grey, corporate consensus. People sat in the orgone box, whose empty chamber reflected the political vacuum in which the left then found itself, hoping to dissolve the toxic dangers of conformity, which, as Reich had eloquently suggested as early as 1933, bred fascism. As Michael Wreszin put it in his 1994 biography of Dwight Macdonald, who promoted Reich’s ideas in his anarchist-pacifist magazine Politics and hosted nude cocktail parties and orgies at his Cape Cod retreat: “In the gloom of the cold war years intellectuals whose historicism had been shaken faced the choice of either accommodating themselves to a prosperous anti-communist society or taking a stand directly on what Mailer, citing Reich, called ‘the rebellious imperatives of the self’.”

Mailer’s debt to Reich was clear when he described, in his essay “The White Negro” (1957), how the hipster “seeks love . . . love as the search for an orgasm more apocalyptic than the one which preceded it”. The hipster – stoked up with marijuana, existentialism and Reich (his God, Mailer wrote, was “energy, life, sex, force . . . the Reichian’s orgone”) – was the prototype of the countercultural figure that emerged in the 1960s. Mailer dismissed psychoanalysts as “ball shrinkers” – the hipster didn’t need to dissect his desires on the couch because the “orgasm is his therapy”. Man, Mailer wrote, “knows at the seed of his being that good orgasm opens his possibilities and bad orgasm imprisons him”.

Mailer built several variants of the orgone accumulator in his barn in Connecticut. One was carpet-lined so that he could scream his lungs out inside, as he combined Reich’s ideas with Janov’s primal scream therapy; others were built like huge dinosaur eggs so that he could roll about inside them. “They were beautifully finished,” remembered Mailer’s friend, the theatre producer Lewis Allen, “and there was a big one that opened like an Easter egg. He climbed inside and closed the top . . .”

Just before he died, Mailer spoke to me about the direct influence Reich had on his thinking: “The Function of the Orgasm was like a Pandora’s box to me,” he said. “It opened a great deal because I had – to speak personally – I’d been struck with an itch in my own orgasm. So much was good in it; so much was not good in it. And his notion that the orgasm in a certain sense was the essence of the character, which came out and was expressed in the orgasm, gave me much food for thought over the years. So there were many years when I felt that, to a degree, when your orgasm was improving, you were improving with it . . . What was important to me was the force, and clarity and power of [Reich’s] early works, and the daring. And also the fact that I think in a basic sense that he was right.”

Irving Howe, the editor who had published “The White Negro” in Dissent, dubbed Mailer the “thaumaturgist of orgasm”. His essay initiated what Dan Wakefield, in his memoir of New York in the 1950s, called “the Great Orgasm Debate”, which raged “not only in the pages of Dissent but in beds all over New York”. In a subsequent issue of Dissent the writer Ned Polsky argued that hipsters were “so narcissistic that inevitably their orgasms are premature and puny”. The orgasm became a battleground: was the “apocalyptic orgasm” the key to revolution, as Reich and Mailer claimed, or a false aim that camouflaged the hipster’s narcissistic and hedonistic selfishness? Mailer admitted that the apocalyptic orgasm had always eluded him; after our interview he phoned me to assert that “intellectuals never had good orgasms”.

In 1947, after Harper’s magazine introduced Reich to mainstream Americans as the leader of “a new cult of sex and anarchy” that was blooming along the west coast, where Henry Miller and other bohemians lived in shacks along the Pacific, the Food and Drug Administration began investigating Reich for making fraudulent claims about the orgone energy accumulator. In 1954, a court ruled that he had to stop hiring out and selling his machine. By that time Reich had started to suffer from paranoid delusions that the world was under attack by UFOs. The armour-clad orgone box was always something of a protective shield, illustrative of Reich’s sense of being besieged, but he now built a “cloudbuster”, an orgone gun that was designed not only to influence the weather – diverting hurricanes and making it rain in the desert – but to be the first line of defence against an alien invasion. It was a kind of orgone box turned inside out, so that it could work its therapeutic magic on the cosmos.

When Reich broke the injunction, continuing to profit from the sale and rental of accumulators, he was sentenced to two years in prison. The remaining boxes were destroyed and thousands of copies of the journals and the 11 books that Reich had self-published in America, which were thought to constitute “false advertising” for his spurious cancer cure, were incinerated, as his books had been in Nazi Germany. These included copies of The Mass Psychology of Fascism and The Sexual Revolution, which made only passing reference to orgone. The American Civil Liberties Union protested against the book-burning, but the paranoid and anti-communist Reich suspected that the organisation was riddled with subversives and refused their offers of help.

On 3 November 1957 Reich died of a heart attack in Lewisburg Federal Penitentiary, eight months into his sentence and just days before his parole hearing. If his claims for the orgone accumulator were no more than ridiculous quackery, as the FDA doctors suggested, and if he was just a paranoid schizophrenic, as one court psychiatrist concluded, why did the US government consider him such a danger? The FDA spent an estimated $2m investigating and prosecuting Reich. In The Chemical Feast, the consumer advocate Ralph Nader’s 1970 report on the FDA, the body was criticised for expending an inordinate portion of its limited resources on “great quack campaigns”, such as the “vicious” pursuit, carried out with “frightening rigour”, of Reich. What was happening in cold war America that led Reich to become an emblem of large-scale fear?

His lifelong obsession with the curative powers of the orgasm no doubt played a part in the FBI and FDA’s dogged pursuit of him. In 1954 the American Medical Association, which had encouraged the FDA to bring Reich to court, accused Kinsey of sparking a “wave of sexual hysteria” with the publication of his 1953 report, Sexual Behavior in the Human Female. If Kinsey’s libertarianism was attracting attention, bringing Reich to trial promised to help stem that tide; popular magazines certainly fused the projects of the two men, seeing in them a communist plot to bring down America. Reich became the scapegoat for the new morality because, as the guru of the “new cult of sex and anarchy”, he seemed to give a philosophical purpose to the data identified by Kinsey. But Reich was an unwitting guru, far removed from the avant-garde who eagerly consumed his ideas on both coasts; he lived a largely reclusive life in rural Maine, surrounding himself with a very few disciples.

Even so, Reich’s ideas certainly became a rallying point for a new generation of dissenters, and his orgone box, however unlikely an idea it may now seem, became a symbol of the sexual revolution. But it was also a symbol of how the use of images of sexual liberation to sell things had become big business; when it was realised that new sexual attitudes couldn’t be contained, they were exploited. In January 1964, Time magazine declared that “Dr Wilhelm Reich may have been a prophet. For now it sometimes seems that all America is one big orgone box”:

With today’s model, it is no longer necessary to sit in cramped quarters for a specific time. Improved and enlarged to encompass the continent, the big machine works on its subjects continuously, day and night. From innumerable screens and stages, posters and pages, it flashes larger-than-life-sized images of sex. From countless racks and shelves, it pushes the books that a few years ago were considered pornography. From myriad loudspeakers, it broadcasts the words and rhythms of pop-music erotica. And constantly, over the intellectual Muzak, comes the message that sex will save you and libido make you free.

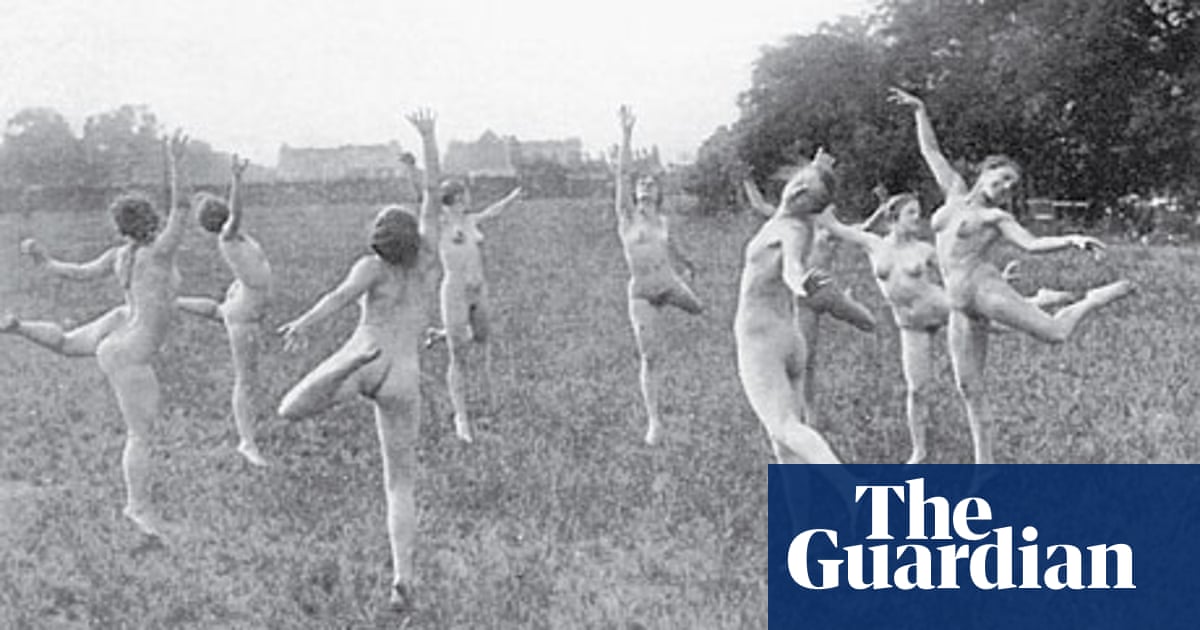

Time called this new “sex-affirming culture” the “second sexual revolution” – the first having occurred in the 1920s, “when flaming youth buried the Victorian era and anointed itself as the Jazz Age”. In contrast, the children of the 1960s had little to rebel against and found themselves, Time commented, “adrift in a sea of permissiveness”, which it attributed to Reich’s philosophy: “Gradually, the belief spread that repression, not licence, was the great evil, and that sexual matters belonged in the realm of science, not morals.” In 1968, student revolutionaries graffitied Reichian slogans, and in Berlin copies of The Mass Psychology of Fascism were hurled at police. At the University of Frankfurt, ’68ers were advised: “Read Reich and Act Accordingly!”

Advertisers, the political theorist Herbert Marcuse argued, eagerly exploited for profit the new realm of unrepressed sexual feeling and used psychoanalysis to encourage the consumer’s apparently infinite desires and to foster what he called “false needs”. Radical sexuality, for which he and Reich had previously held grand hopes, was co-opted and contained: the libido was carefully, almost scientifically, managed and controlled. In the process, as Marcuse detected, sex and radical politics became unstuck.

The orgone energy accumulator offered a generation the opportunity to shed their repressions by climbing into a box, which in turn served as an apt symbol of their alienation and new imprisonment. It is perhaps significant that in Sleeper the Orgasmatron – a machine in which the Woody Allen character attempts to hide from the secret police – is the product of an authoritarian regime. Similarly, in Roger Vadim’s Barbarella (1968), the evil scientist Durand-Durand, who seems to be partly based on Reich, uses a form of orgone accumulator as an instrument of torture when he attempts, unsuccessfully, to kill Jane Fonda with pleasure. These films might be seen to contain, hidden within their comedy, the sort of doubts raised by Marcuse about the efficacy of the sexual revolution. Sexual pleasure, they appear to argue, is not always revolutionary, but can be offered by the establishment as a panacea, thus becoming in itself a form of repression.

As Aldous Huxley wrote in his 1946 preface to Brave New World, a novel about a futuristic dystopia in which sexual promiscuity becomes the law, “as political and economic freedom diminishes, sexual freedom tends compensatingly to increase. And the dictator . . . will do well to encourage that freedom . . . it will help to reconcile his subjects to the servitude which is their fate.” Sexual liberation, despite its apparent eventual successes, might be interpreted, as the philosopher Michel Foucault suggested (with reference to Reich), as having ushered in “a more devious and discreet form of power”.